Science and film are not a mixture that most people associate with. Sure, there’s all the cliched talk of the crazy world, but when it comes down to it Act Cinema The average citizen does not realize the amount of science involved.

(Credit: United Artists)

We have all the science and engineering of digital cameras, the chemistry of films in the film, you could spend an entire day recounting everything that science contributes to cinema, but in our particular case, we were able to see the fruits of the application on screen physics and mathematics. , in an exciting scene immortalized in the annals of cinema.

It was 1974, the movie was 007 against the man with the golden pistol. The producers were trying to create interesting and exciting scenes for the movie, until driver Joey Chitwood at a stunt meeting suggested to Jay Hamilton, the director, a stunt called Astro Spiral Leap, which was done in Houston, at an event named American Thrill Showkind of exciting car show.

Good to Be Bond (Credit United Artists)

Jay Hamilton liked the idea, and pitched it to film producer Albert R. It was a Chtwood fiasco, but Hollywood (I know!) is like that.

Such a maneuver was never used in a movie, and it was impressive: a car accelerated toward an inclined slope, turned 360 degrees and landed on another slope with the opposite slope. Any decent pilot, hearing the description of the maneuver, will say that it is impossible. And it was, except for the computer.

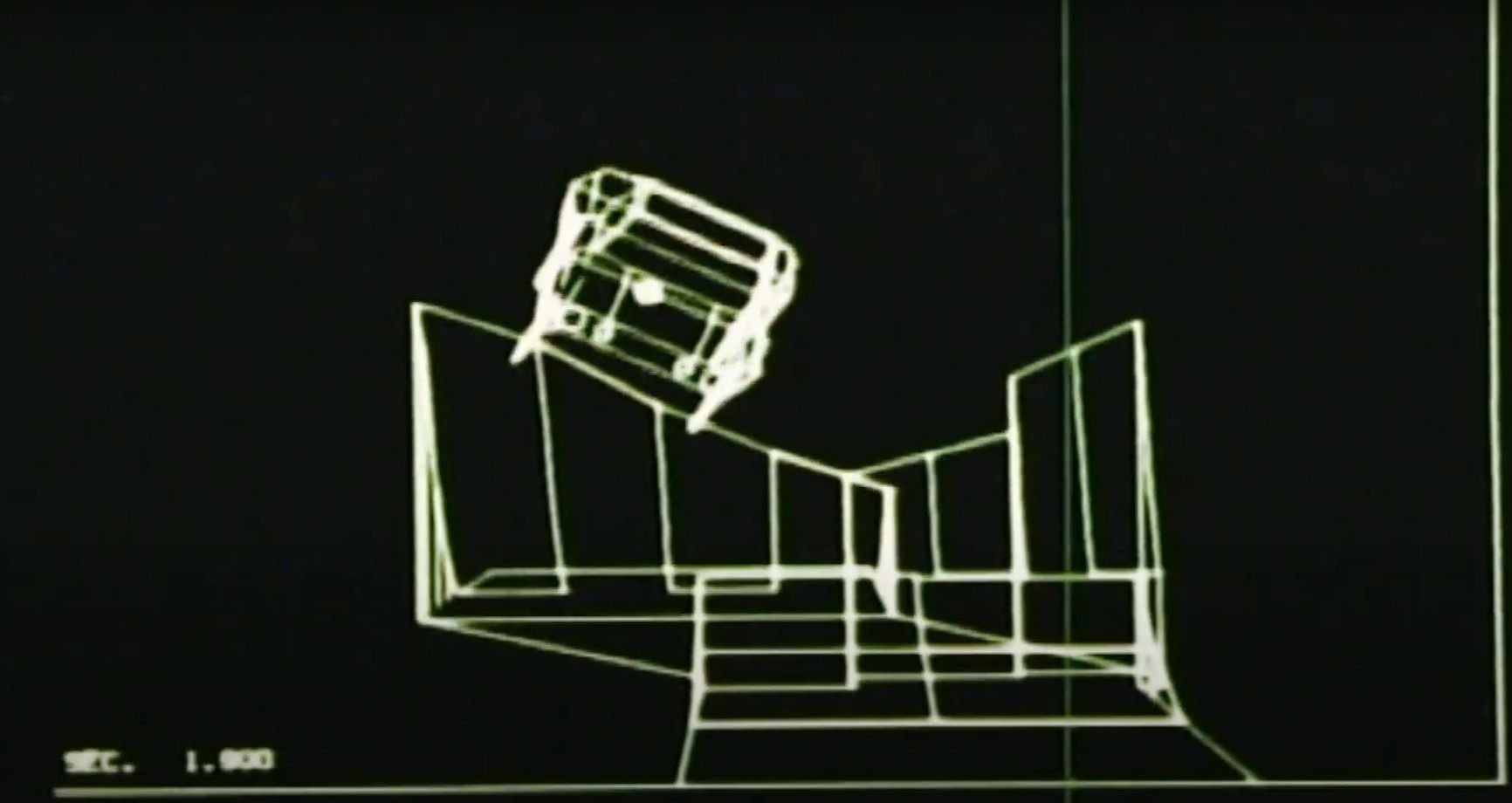

The heyday of computer graphics in 1968. No, it wasn’t Ray Tracing (Credit: CAL)

The Astro-Spiral Leap was credited to Raymond R. McHenry, who worked at Cornell Flight Laboratory. By 1968 he and his team were writing software in the Fortan language to simulate the behavior of vehicles. They had a small fleet of cars full of sensors to validate their models. One day, a traveling show led by Joey Chitwood arrives in town. McHenry hired some pilots to perform daring stunts, give hobby horses, ride two wheels and the like, to collect data and improve his software.

The conversation goes on, and the conversation is good, the old desire for a helical jump emerges, something everyone wanted to do but realized was impossible. McHenry decided to try designing a jump on his IBM 390 with a punch card.

IBM 360. They generally came with memory up to 1 MB, and they can be expanded up to 8 MB. Crysis is not running. (credit: IBM/Wikimedia Commons)

The basis of the McHenry system was Euler equations involving the movement of inanimate objects. They consider torque, acceleration, moment of inertia, and many other variables to predict the behavior of inanimate objects.

The project was a success, the audience loved the maneuver but it was a very local thing, at most watched on TV quickly and forgotten, but James Bond will immortalize this little victory for science…

Producers were warned that it was not just a matter of creating a similar ramp. McHenry was called in and all the math had to be reconstructed. The car was an AMC Hornet X, which needed a model. To keep the center of gravity as central as possible, the car was modified and the steering column was placed in the center rather than to the left of the car.

Parts of the chassis were enlarged to redistribute weight, and a rigid wheel was installed in the middle of the rear axle to increase torque and make jumping possible.

McHenry’s team computed the matrices with more than 10 independent variables, until they arrived at the ideal values: 40 mph (about 64 km/h) of speed, 1,450 kg of mass, 200 degrees per second of rotation, plus the slope of the slopes, and the distance between them , etc., etc., etc., etc.

The day came, June 1, 1974, the team is now in rural Thailand. Inside Hornet, sandwiched between two models dressed as Bond and Sheriff Bieber, acrobatic pilot Lauren “Bumps” Willert, bent on keeping the speedometer at exactly 40 mph (about 64 km/h).

The scene cost a fortune but the producers were shot in the arm. dsclp. (credit: United Artists)

It’s time to find out if the flag is true, or if it should be fished from the bottom of the channel. Well, the science was in place, the Hornet did a great 360, and landed just over the other side of the slope. The director was ecstatic, the entire crew applauded, including the audience of 100 journalists whom the producers brought from Europe in a chartered 747 to watch the jump.

Of course, being journalists, upon the appearance of the film many who witnessed the jump praised the “special effects” of the scene.

The Gambit entered the Guinness Book and won up to A paper (Warning, PDF) By Raymond McHenry detailing the process. Ironically, there is a group of Luddites who say they hate using computers in the cinema, and prefer vintage practical effects, and this group doesn’t know that one of the biggest practical effects was possible only thanks to a lot of science and many hours of computing.

“Hardcore beer fanatic. Falls down a lot. Professional coffee fan. Music ninja.”

More Stories

The law allows children and adolescents to visit parents in the hospital.

Scientists pave the way for the emergence of a new element in the periodic table | World and Science

Can dengue cause hair loss? Expert explains how the disease affects hair