It’s not just the Pyramids of Giza that are facing scientific scrutiny and becoming shrouded in a lot of mysticism – the Great Sphinx of Giza, which shares a site with the ruins, has also been extensively studied by archaeologists, not to mention pausing. In a new study, researchers show that the ancient Egyptians received outside help in building the Sphinx, but quietly: not from aliens, but from desert winds!

It all started when the team noticed rare rock formations found in deserts around the world, called yardang. They are formed as a result of erosion caused by winds, and end up with a shape and proportion similar to that of the Great Sphinx.

The work continued to reproduce the relevant climatic conditions in the laboratory, to show that the final touches would be sufficient to give the legendary face to the rock near the three most famous pyramids in Egypt.

Sculptures made by the wind

The Egyptian Sphinx is a creature of mythology, showing the head of a human on the body of a lion still bearing the wings of an eagle. But instead of building the largest of them from scratch, it seems the ancient Egyptians only needed to model the details. Scientists point out that some current yardangs have the appearance of animals sitting or lying down, which adds strength to the hypothesis.

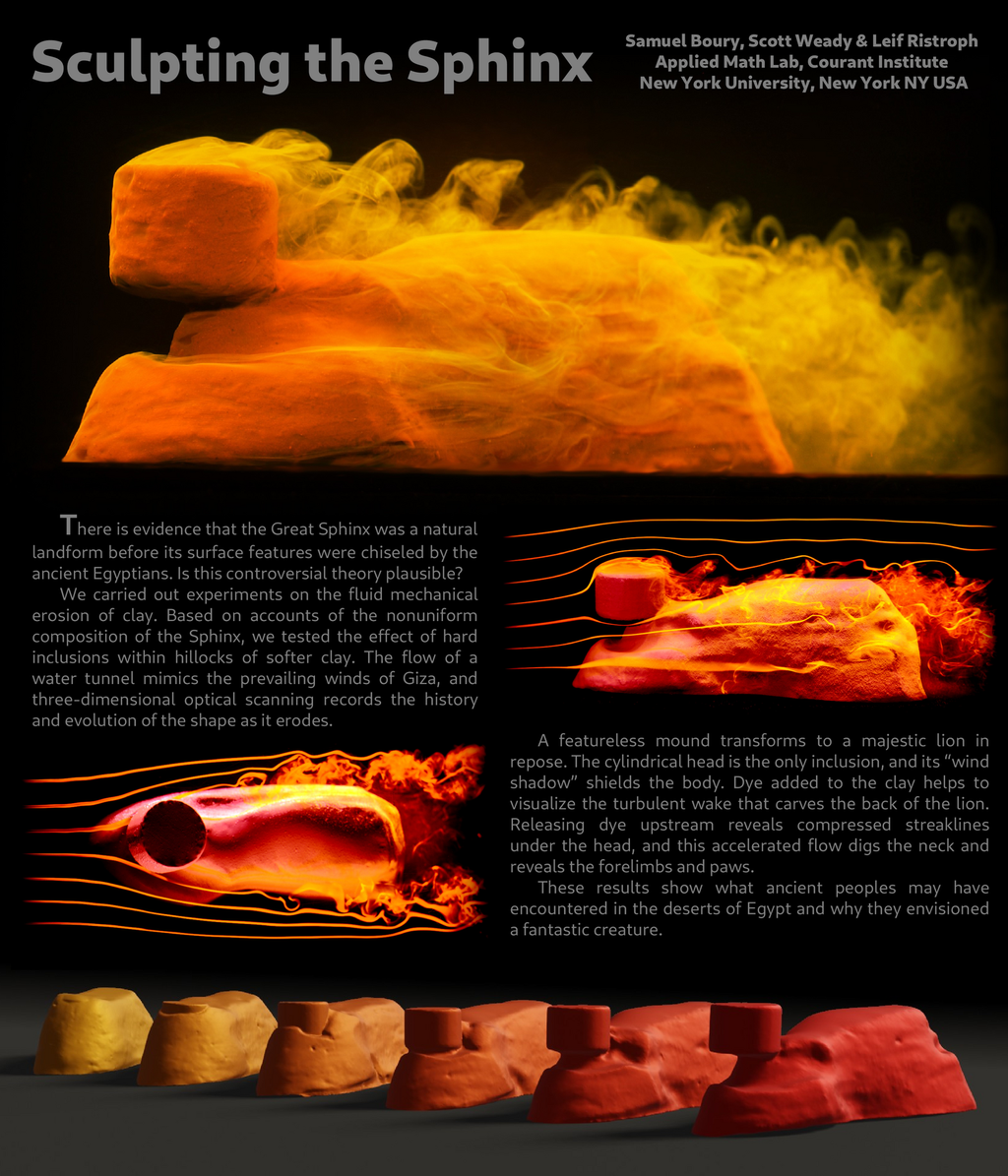

Not only did the scientists rely on inference, they simulated Giza’s topography by building mounds of malleable clay around harder, less erodible materials. These mounds were placed in a water tunnel, simulating the wind conditions of northeastern Egypt, where the Monument to the Cat Hybrid is located.

The impact of erosion, in the scientists’ words, caused “a featureless hill to transform into a majestic lion.” The water moved at high speed and gradually tore up the clay, causing the more resistant material inside to form a cylindrical head, creating a “wind shadow” and protecting the rest of the body.

The statue’s curved back was hollowed out by a “turbulent eruption,” according to scientists, and the accelerating flow below the head formed the statue’s neck, hind limbs, and feet. The unexpected shapes arise from the deflection of wind flows around harder or less erodible parts.

The team concluded the study by referring to what the ancient people of Egypt found in the middle of the desert, and ultimately imagined and represented a mythical hybrid creature. The work has been accepted for publication and must be included in a scientific journal Physical review fluidswith its abstract presented at the 75th Annual Meeting of the APS (American Physical Society) Fluid Dynamics Section.

source: American Physical Society

“Hardcore beer fanatic. Falls down a lot. Professional coffee fan. Music ninja.”

More Stories

The law allows children and adolescents to visit parents in the hospital.

Scientists pave the way for the emergence of a new element in the periodic table | World and Science

Can dengue cause hair loss? Expert explains how the disease affects hair