Archaeologists working deep in the Amazon rainforest have discovered an extensive network of cities dating back 2,500 years.

Highly organized pre-Hispanic settlements with wide boulevards, long, straight roads, plazas and clusters of archaeological platforms have been found in the Obano Valley in the Ecuadorian Amazon in the eastern Andes, according to a study published in the journal Science this week. ), entitled “Two Millennia of Horticultural Urbanism in the Upper Amazon.”

This is the discovery of the largest and oldest urban network of built and excavated monuments in the Amazon to date, and was the result of more than two decades of investigations in the region by a team from France, Germany, Ecuador and Puerto Rico.

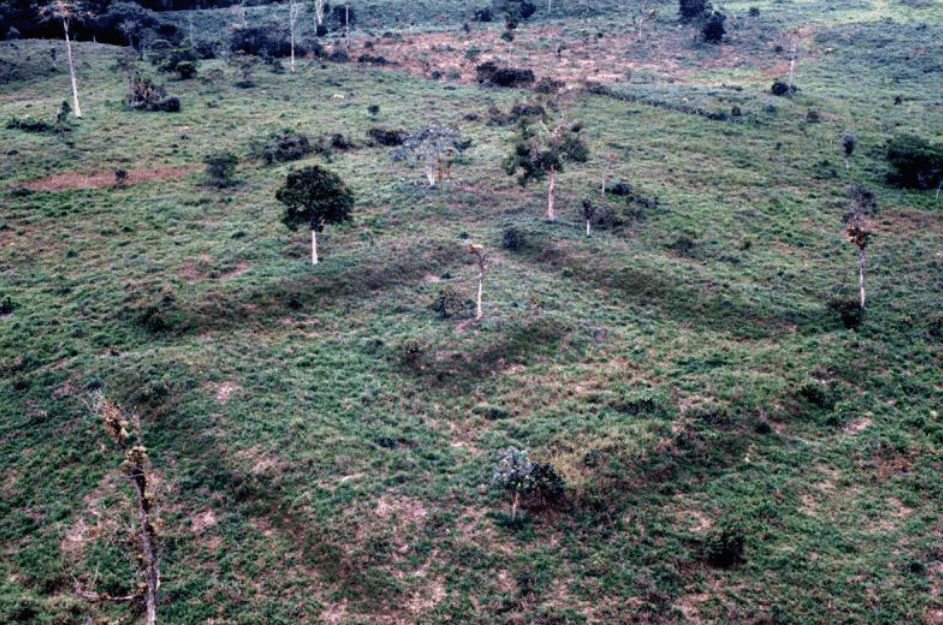

The research began with field work before deploying a remote sensing method called light detection and ranging, called LiDAR, which uses laser light to detect structures beneath thick tree canopies.

The study's lead author, Stephen Rosten, an archaeologist and director of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), described the discovery as “incredible.”

Brazil: Village in Alto do Xingu

In the forest region of southern Amazonia, in the state of Mato Grosso, pre-Hispanic circular villages have been documented in the upper Xingu River. According to the study, they resemble modern villages such as Koikuru, where longhouses (large communal homes) are arranged in a circle.

A huge circular central plaza has been recorded and the largest archaeological sites can have an area of up to 50 hectares, bounded by circumferential ditches ranging from 500 to over 2,000 meters in length. These ditches are defined by high internal resistance where a wooden fence was originally built.

The diameter of the old squares ranges from 120 to 150 metres, and the width of the roads reaches 40 metres. These paths radiate from the central space in different directions to connect with settlements or other sites that may have been important for the residents' livelihood, according to the authors. Major political ritual centers and medium-sized villages as well as small villages without a central square have also been documented. The settlements were separated by rivers up to 10 km long.

“The LiDAR gave us an overview of the area and we were able to really estimate the size of the sites,” he told CNN International, Friday (12), adding that it showed them a “whole network” of excavated roads. “LiDAR was the icing on the cake.”

The first people to live there, 3,000 years ago, had small, scattered homes, Rustin said.

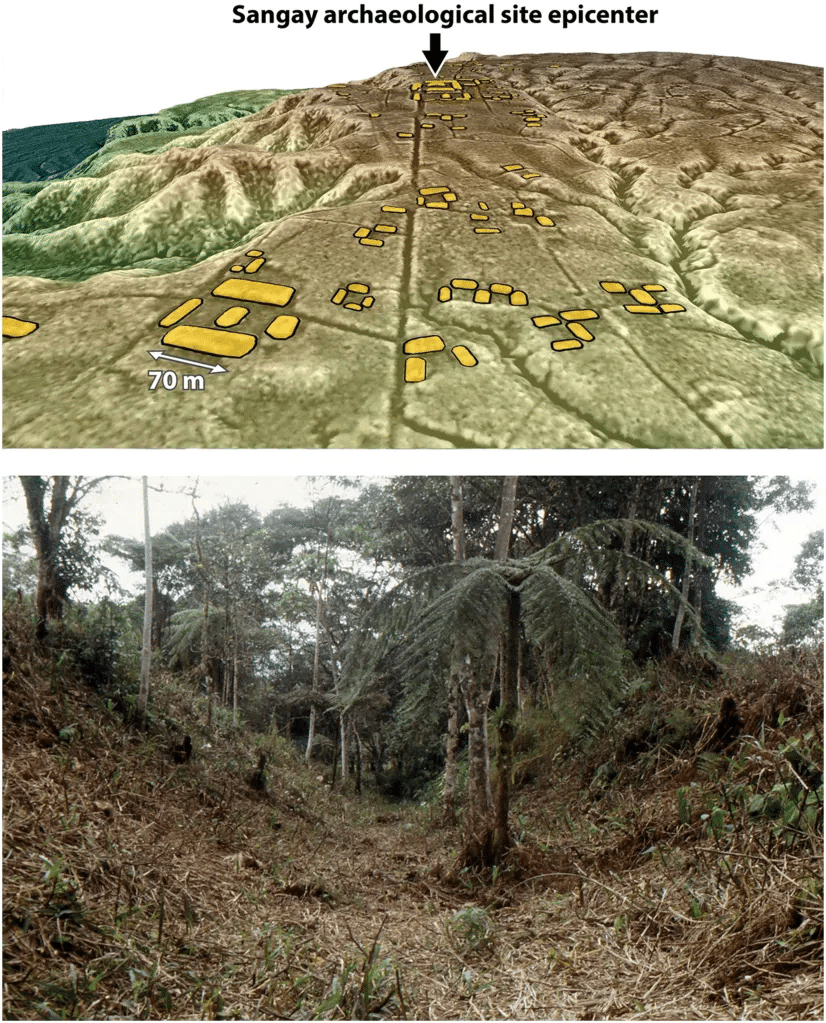

However, between approximately 500 B.C. and 300 to 600 A.D., Kilomobi and later Obano cultures began building mounds and placing their homes on earthen platforms, according to the study's authors. These platforms will be organized around a low square arena.

LiDAR data revealed more than 6,000 platforms in the southern half of the 600 square kilometer surveyed area.

The platforms were mostly rectangular, although some were circular, and their dimensions were about 20 x 10 metres, according to the study. They were usually built around a square in groups of three or six. Squares also often have a central platform.

The team also discovered massive complexes with much larger platforms, which they said likely had a civic or ceremonial function.

At least 15 groups of complexes have been discovered that have been identified as settlements.

Some settlements were protected by ditches, although there were roadblocks near some larger complexes. This indicates that the settlements were exposed to threats, whether external or resulting from tensions between groups, the researchers said.

Even the most isolated complexes were connected by paths and an extensive network of larger straight roads with sidewalks.

In the empty buffer zones between the compounds, the team found farmland features such as sewage fields and terraces. According to the study, it was linked to a network of pedestrian paths.

“That's why I call them garden cities,” Rustin said. “It's a complete revolution in our paradigm of the Amazon.”

“We have to believe that all the indigenous people of the rainforest were not semi-nomadic tribes lost in the forest in search of food. There is great variety and diversity of cases, and some of them were also urban-based, with a caste society,” he said.

The general organization of the cities indicates “the presence of advanced architecture” at the time, according to the study's authors, who conclude that the urbanization of parks in the Obano Valley “provides further evidence that the Amazon is no longer the pristine jungle it once was.” “Depict.”

Rustin said we should imagine the pre-Columbian Amazon “like an anthill,” where everyone is busy with activities.

Similar networks exist in the Americas

This recently discovered urban network corresponds closely with other sites found in the rainforests of Panama, Guatemala, Belize, Brazil and Mexico, according to landscape archaeologist Carlos Morales Aguilar, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved. the study.

He called the study “groundbreaking” and told CNN International that it “not only provides tangible evidence of advanced and early urban planning in the Amazon, but also contributes significantly to our understanding of the cultural and environmental heritage of indigenous communities in this region.”

In 2022, Morales Aguilar was part of a team of researchers who used LiDAR technology to discover a vast site in northern Guatemala, comprising hundreds of interconnected ancient Maya cities, towns and villages, as well as an area 177 kilometers long. A network of raised stone paths connects the communities.

He said the results of this latest study mirror the advanced agricultural and urban planning techniques he observed in northern Guatemala and “offer new insights into the complexities of these primitive societies.”

Credits: CNN.

“Music fanatic. Professional problem solver. Reader. Award-winning tv ninja.”

More Stories

Couple retakes glacier photo after 15 years, surprised by changes: ‘It made me cry’

Two killed in hotel collapse in Germany – DW – 07/08/2024

Lula speaks for half an hour on phone with Biden about Venezuela’s electoral impasse | Politics