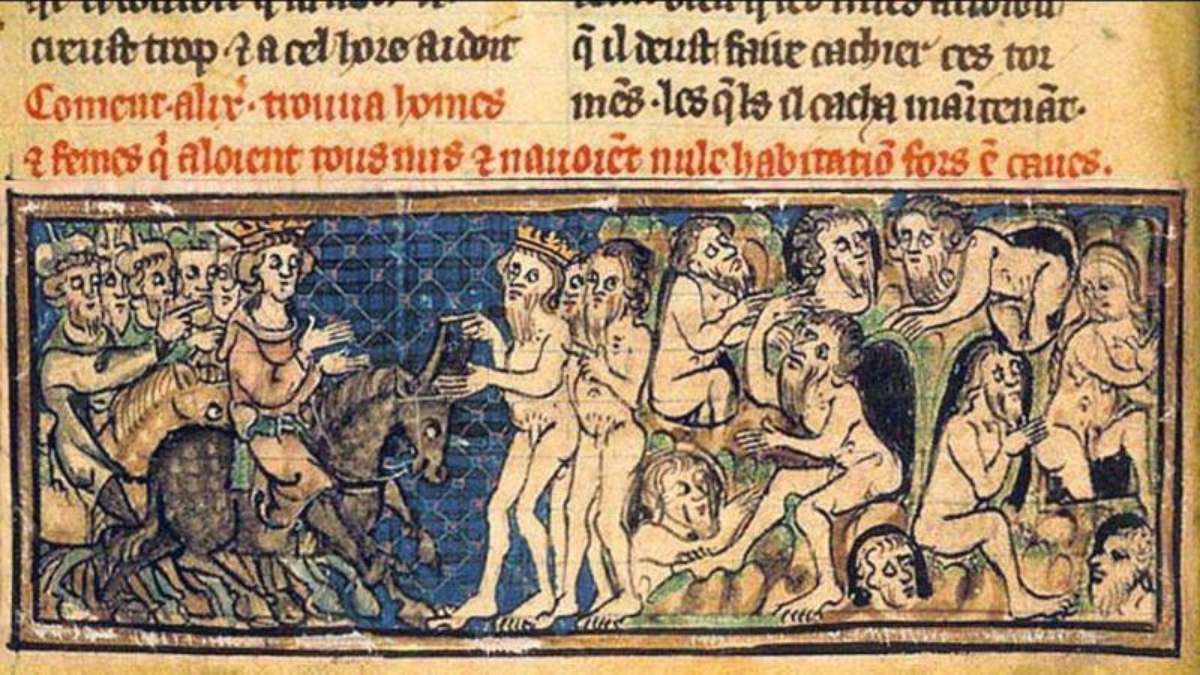

It is said that once upon a time, after conquering Persia nearly 2,300 years ago, Alexander the Great reached the banks of the Indus River and found a gymnast – a naked sage – sitting on a rock, looking up at the sky.

Alexander asked, “What are you doing?”

The gym replied, “You suffer from nothingness.”

“and what are you doing?”

Alexander replied: “Conquer the world.”

The two laughed, each thinking the other was a fool wasting his life.

The famous Indian mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik recalls this story to illustrate the differences between Indian and Western cultures—and also to show how philosophically open India was to the concept of nothingness long before the number zero was written.

fire

The three great religions of ancient India – Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism – retained an exceptional focus on numbers.

The history of Indian mathematics dates back to the Vedic period (c. 800 BC), when religious practice required very complex calculations.

At that time, rituals were an important part of people’s lives. The construction of altars of fire was governed by precise specifications detailed in ŚulbasūtrasIndia’s oldest scholarly texts.

Written between 800 BC and 200 BC, W Śulbasūtras It contains, among other things:

– Transforms geometric shapes, such as square to circle or rectangle to square, keeping the same areas. For this, it was necessary to calculate the value of the number pi (π);

– calculating the square root of 2 (2), the irrational number that would threaten Pythagorean philosophy;

– And speaking of Pythagoras, Indian writings already included the theorem that bears his name, 200 years before the Greek philosopher and mathematician was even born.

giants

In addition to advances in engineering, the Indians developed a unique old-world obsession for sheer numbers.

In Greece, the largest number was the uncountable, representing 10,000. But India reached trillions, quadruples, and beyond. Remnants of that ancient passion for the impossible mega-major live on to this day.

“Very large numbers are part of the talk,” says Indian mathematician Shrikrishna G. Dani.

For example, if you sayBadarthaWithout explanation, almost everyone understands.

Badartha?

It’s 10¹⁷ – 1 followed by 17 zeros [100.000.000.000.000.000, ou 100 quatrilhões] – It literally means “halfway to heaven,” explains the professor.

“And in the Buddhist tradition, numbers have gone much further: 10⁵³ is one of them.”

But why these numbers? Are they used for something?

“There is no obvious practical reason,” says Danny.

“I think there’s a certain kind of satisfaction that people feel when they think about those kind of numbers.”

What better reason than satisfaction!

The Jains were not far behind either. Raju, for example, is the distance covered by God in six months, after covering 100,000 yojanas in each blink of an eye.

This explanation probably doesn’t tell you anything, but when you do a rough math, if God blinks 10 times a second, he’s traveling about 15 light years.

No Western religious text mentions anything close to this.

And as if this were not enough, the Indians thought of and classified many types of infinity, which were fundamental to the development of abstract mathematical thinking two thousand years later.

From nothing to zero

Of course, to imagine that many zeros, you had to invent them first.

The concept of emptiness was already present in many cultures. For example, the Mayans and Babylonians used signs of absence of quantity. But it was the Indians who turned this absence into zero, they called it Shunya (“empty” in Sanskrit).

Giving a symbol for nothing, and saying, in other words, that nothing was a thing, was perhaps the greatest conceptual leap in the history of mathematics.

But when did this jump happen?

Until a few years ago, the oldest zero ever found was that found on a temple wall at Gwalior Fort in central India. It dates back to 875 BC, but at that time, the zero was already in common use in the region.

As of 2017, the first recorded mention of zero is in an ancient Indian scroll known as the Bhakshali Codex. It has been carbon-dated to the third or fourth century – but some experts do not accept this dating.

In any case, as far as we know, the Indian astronomers and mathematicians Aryabhata, born in 476, and Brahmagupta, born in 598, were the first to formally describe the decimal places and the current rules governing the use of the number zero, attesting to their amazing usefulness.

The Indian numerical system outdid others in the way it facilitated calculations, and spread first through the Middle East, and later reached Europe and the rest of the world, until it became the dominant system.

But why did zero originate in India? Was it just a matter of writing large numbers, or were there other spiritual forces at play?

Nirvana

“The interesting thing is that there are a lot of them Shunya popped up everywhere. It has been around since about 300 BC,” according to historian of mathematics Georg Gerghesi Joseph.

highlights that Shunya He was present in “architectural manuals, saying that the important thing was not the walls, but the space between them,” and even “the belief that exists in Buddhism, Jainism, primitive and fundamental religion that you need to reach a certain state called nirvana, where everything is erased.”

“It was a very fertile environment for someone whose name we do not know, to realize that this philosophical and cultural concept would also be useful in a mathematical sense,” says the historian.

For mathematician Renu Jain, vice-chancellor of Devi Ahilya Vishwadevialaya University in India, there is no doubt that the spiritual idea of nothingness inspired the mathematical idea of zero.

“Zero does not denote anything, but is derived in India from a concept Shunyaa kind of salvation, a qualitative pinnacle of humanity, in a sense,” he explains.

When all our desires are fulfilled, we have no desires and then we go to nirvana or Shunya. “

In other words, nothing is all.

In fact, the very use of the circle to denote zero may have religious origins.

“The circle also symbolizes the sky,” notes Indian mathematics historian Kim Plovker.

He explains that “Many of the words used to orally symbolize zero in Sanskrit mean heaven or emptiness. Therefore, since heaven is represented by the circle of heavens, this is a very appropriate symbol for zero.”

“According to the religions of India, the universe was born out of nothing, and nothingness is humanity’s ultimate goal,” mathematician Marcus du Sautoy said in the episode. Eastern genius (“Genius of the East”) from the TV series Mathematics story (“History of Mathematics”), BBC.

“So perhaps it’s not surprising that a culture that passionately embraces emptiness can easily internalize the idea of zero,” he says.

We can never say with complete certainty, but according to the opinions of various experts, it is likely that something in the spiritual wisdom of India led to the invention of zero.

Another idea related to zero and emptiness has had a profound impact on the modern world.

Computers operate on the principle of two possible states: on and off. When connected, the value is set to 1; And when it’s off, it’s 0.

“Perhaps not surprisingly, the binary number system was also invented in India in the second or third century BC by a musicologist named Pingala, despite his use of the metre,” historian of science and astronomy Subhash Kak told BBC Travel journalist Marilyn. Ward.

And the belief that everything was born in India… out of nowhere!

Listen to BBC Radio 4’s programme.Nirvana by the numbers(in English), which gave rise to this report, on the website BBC Sounds.

“Hardcore beer fanatic. Falls down a lot. Professional coffee fan. Music ninja.”

![[VÍDEO] Elton John’s final show in the UK has the crowd moving](https://www.tupi.fm/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Elton-John-1-690x600.jpg)

More Stories

The Director of Ibict receives the Coordinator of CESU-PI – Brazilian Institute for Information in Science and Technology

A doctor who spreads fake news about breast cancer is registered with the CRM of Minas

The program offers scholarships to women in the field of science and technology