British scientists have discovered the fossil of the oldest known predator.

The 560-million-year-old specimen, found in the Charnwood Forest in Leicestershire, is likely a precursor to cnidarians – the group of animals that today includes jellyfish.

The researchers named the fossil Auroralumina attenboroughii. It is a tribute to naturalist David Attenborough, historical BBC presenter.

The first part of the name is a reference to a Latin expression meaning “dawn of the lantern.”

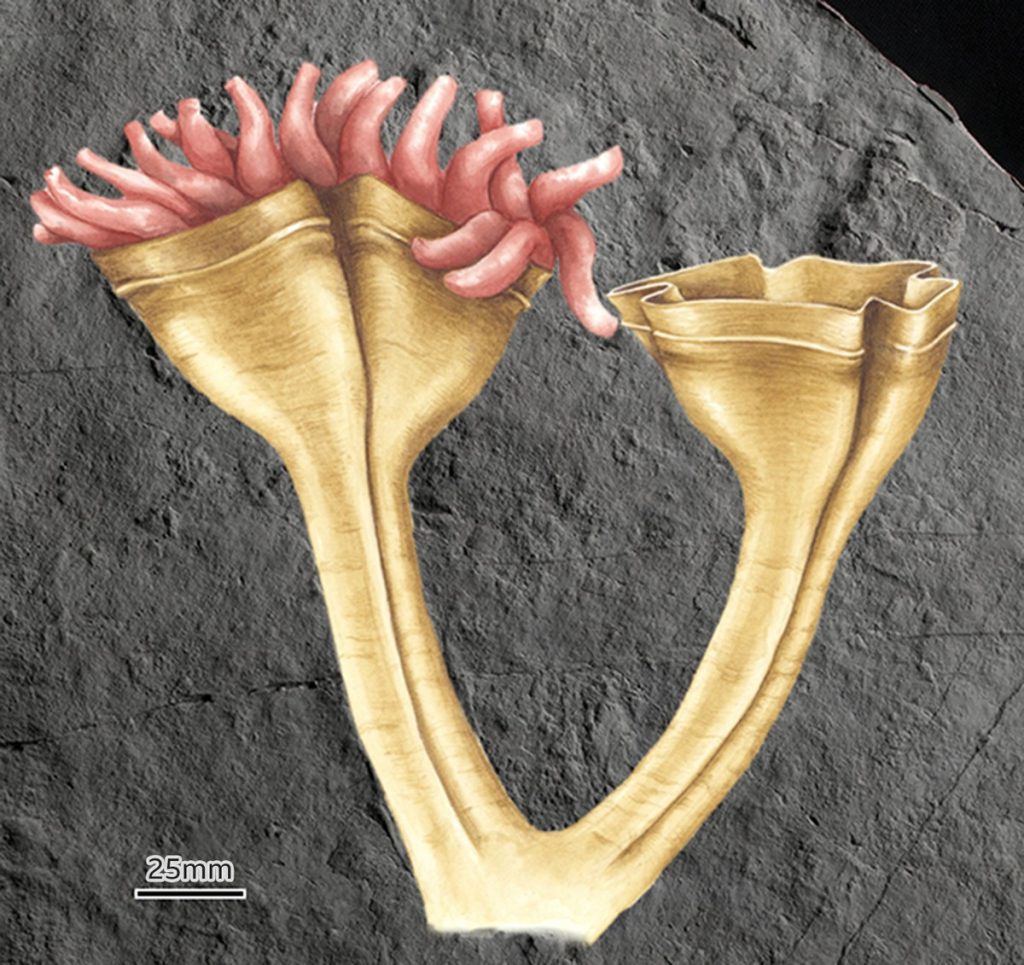

“I think it looks like an Olympic torch, and its tentacles are flames,” says Frankie Dunn of Oxford University, who wrote an article about the discovery in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Not only does the fossil prove that predation existed in the animal kingdom about 20 million years earlier than previously thought, it is also likely the first example of such an organism with a true skeleton.

The outline of the 20 cm high creature stands on a long sloping slab of a quarry, surrounded by other fossils.

All of them are believed to have been buried by a stream of sediment and ash flowing down the undersea flank of an ancient volcano.

The area where the fossil was originally located was discovered in 2007, when researchers cleaned the rocky face of the Charnwood with high-pressure hoses.

It took 15 years to understand the site – only then did they find the exact location where Auroralumina was.

Leicestershire is famous for what it tells us about the period known as the Ediacaran (635 to 538 million years ago).

This is the period of geological history immediately preceding the Cambrian, which saw a huge explosion in the number and diversity of life forms on Earth.

In the Cambrian period (between 538 and 485 million years ago) the ‘model’ was set for many modern animal groups.

But Auroralumina proves that their group, the Cnidarians, has a heritage that extends farther back, all the way to the Ediacaran.

Phil Welby, Head of the Department of Paleontology at the British Geological Survey, explains: “It is a strong indication that there were more recent-looking creatures in the Precambrian. This means that the ‘wick’ of the Cambrian explosion was probably very long.”

While the name “cnidaria” may not be quite as familiar, the animals that fall into this category are all too familiar: corals, jellyfish, and anemones. One of their features is the stinging cells they used to capture their prey.

Dunn’s analysis of Auroralumina features links the animal to the medusozoa subgroup within cnidarians.

Medusozoans go through several stages during their complex life cycles. In one of them, it looks like a mass anchored to the sea floor. Later, they transform into floating creatures in the breeding season.

During this floating stage, they take the form of an umbrella with stinging tentacles. They have become a kind of jellyfish.

Thus, Auroralumina is very similar to the Medusozoan in its rooted stationary phase.

“What’s really exciting is that the animal is forked. So you have these two ‘cups’ stuck near its base, and there was a continuous bit of the skeleton going down to the sea floor, but that piece we didn’t find. Unfortunately, the fossil is incomplete,” Dan said.

Bifurcation – splitting into two branches or parts – is another novelty in the newly discovered fossil.

Paleontologists from all over the world visit the Charnwood Forest.

Its main attraction is the fossil known as Charnia masoni.

This was found in the 1950s by two students – Roger Mason and Tina Negus – and was the first Precambrian fossil to come to light.

The animal was likely buried in a slice of sediment in the underwater part of the volcano – Photo: BGS/UKRI

The charnia was later also found in the rocks that make up the Ediacaran Hills in Australia, which gave its name to the Ediacaran period.

It has a strange-looking life-form resembling a fern leaf, but scientists are convinced that it was indeed some kind of animal.

There is also an example of an Oralumina measuring only 40 cm in the same location.

The name David Attenborough was used to name the animal because it originated in this central part of England.

“When I was at school in Leicester, I was an avid fossil hunter,” he recalls.

“The rocks in which Oralumina was discovered were so old that they date back to long before the beginning of life on this planet. So I’ve never looked for fossils there,” he said.

“A few years later, a boy at my old school found a fossil and proved the experts wrong. He was rewarded: his name was used to name the find. Now I almost caught up with him and am really happy,” Attenborough says.

This text was published in https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/geral-62300687

“Music fanatic. Professional problem solver. Reader. Award-winning tv ninja.”

![[VÍDEO] Elton John’s final show in the UK has the crowd moving](https://www.tupi.fm/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Elton-John-1-690x600.jpg)

More Stories

A South African YouTuber is bitten by a green mamba and dies after spending a month in a coma

A reptile expert dies after a snake bite

Maduro recalls his ambassador to Brazil in a move to disavow him and expand the crisis