The International Astronomical Union announced this week that researchers Lennart Lindgren of Lund University in Sweden and Michael Berryman of the University of Dublin in Ireland have been awarded this year’s coveted Shaw Prize for astronomy.

The two are honored for their work on the Hipparcos and Gaia space missions, which produced the best maps we have of our galaxy, which I consider a good opportunity to explain a little bit how to obtain and use this data.

The two missions were launched by the European Space Agency: Hipparcos in 1989, and Gaia, its successor, in 2013. While the first mission cataloged just over 100,000 stars, the second should monitor and track a billion objects.

Both work in a similar way, measuring with high accuracy the position of each indexed star. This list then becomes an important reference for the rest of the astronomical community, who can now use these indexes as a map to determine the position of other objects in their images.

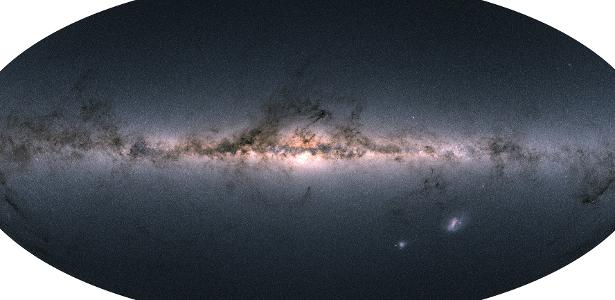

Gaia went much further, thanks to his ability to observe faint objects. Thus, unlike Hipparcos, he was not limited to the solar region, but was able to measure the location of stars in neighboring galaxies hundreds of thousands of light years away.

However, the power of these telescopes is greater. It not only measures the position of the stars, but is also able to measure the distance between them, which is always a challenge.

Stars, for astronomers, are always small bright spots in the sky, and it is impossible to measure the distance to them directly. As for the apparent brightness, it can be a very bright and very far away star, or a fainter and closer star.

To solve the problem, one of the main methods used is parallax. Imagine you see an airplane in the sky. An airplane taking off, close to the ground, appears to be moving much faster than an airplane in the sky, due to the great distance between you.

Hipparcos and Gaia used the same geometric principle, but using the apparent change in the position of the stars as the Earth revolves around the sun. The closer the star is, the more it appears to move across the sky throughout the year.

As you can see, this change is very small. Something like a friend of yours taking two steps to the side…on Venus! Imagine being able to detect such a subtle change of situation. This is the power of the Gaia satellite.

Because we know exactly Earth’s distance from the sun, we can triangulate to determine the distance to every star in the catalog, effectively creating a 3D map of the billion stars around us.

It’s not just an impressive achievement, but something very useful for all areas of astronomy.

A well-deserved award and beautiful recognition for these high-impact projects. Next year, who will win? Maybe those responsible for the black hole image?

![[VÍDEO] Elton John’s final show in the UK has the crowd moving](https://www.lodivalleynews.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Elton-John-1-690x600.jpg)

More Stories

What ChatGPT knows about you is scary

The return of NFT? Champions Tactics is released by Ubisoft

What does Meta want from the “blue circle AI” in WhatsApp chats?